‘In this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes’.

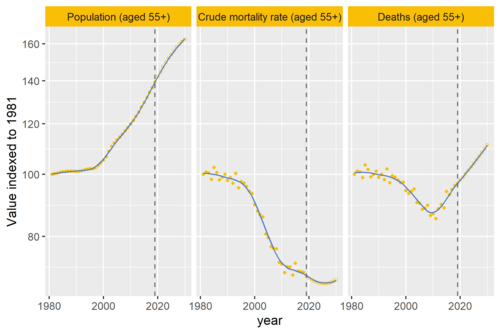

The absolute number of deaths in the UK is rising, as our population ages, and as Benjamin Franklin noted, mortality remains stubbornly at 100%. We all die. And we all wish to do so in a manner of our choosing, likely at home, at peace, and with people we love and trust caring for us.

We don’t all achieve this though, and the type of data in the Strategy Unit’s analysis starts to help us to understand where we might be able to make changes that will improve the quality of care and dying for more people.

There are some startling, and concerning, headline figures. People from deprived areas are more likely to die in hospital, for example. Or that 37% of those who die in hospital do so after an emergency, rather than a planned, admission. The use of A&E in the years before death is high. Patterns of care appear to differ depending on your diagnosis. These patterns indicate inequality, and a trend to care that might be seen as less settled, less planned.

As someone who worked in Worcestershire as a Community Macmillan Nurse the mid-1990s, and then later as the Macmillan Palliative Care Services coordinator, I read this data in light of past personal experience. I saw first-hand that poverty could affect people’s ability to provide care, or the lack of community care overnight could trigger an emergency call. It is shocking that this may still be what underpins some of the figures in this analysis.

But these data only tell a small part of the story. As the Strategy Unit notes, they were not able to access or use data from primary care, from GPs, from social care. I would also add that the whole pattern of care is not visible until we collect data from hospices, and informal carers.

We know that, despite hospital use increasing as someone is closer to death, nevertheless people still spend most time in their usual place of residence. It is likely that the care that people receive at home from GPs, from district nurses, from social care, from specialist palliative care services, from volunteers and the community, and most importantly from their own family and friends is likely what makes most difference to people.

Gaps in this care are also likely to trigger some of the emergency admissions we see in these hospital data. Doing something to change hospital care is not going to change why people turn up in an ambulance in the middle of the night. Emergency admissions have been categorised as: the “palliative care” emergency (such as a spinal cord compression), the “normal” emergency (such as a heart attack, or fracture) , and the “perceived” emergency1. It is the perceived emergency that may be an issue – where people perhaps panic at home because they don’t know what to do, they don’t know how or who to contact for advice.

These data are powerful, but perhaps as much for what they don’t tell us, as what they do. We need to agitate for whole systems data, that tell us more about the patterns (and gaps) in care that people receive across the years before they die. Much of this will not be in institutions.

And we can also see how important qualitative data might be – the narratives of people who are experiencing care – to help unpick these data. As an example, it is perfectly clear from powerful interview data that hospital care is not necessarily a bad thing. It can be a place of peace, safety and refuge2.

Let us keep collecting (better) data and use it as a tool for change, so that in another 20 years I can look back and continue to see real improvements in care and experience.

Catherine Walshe is a Professor of Palliative Care at the International Observatory on End of Life Care at Lancaster University.

She can be found on twitter @cewalshe, and more about the work of the team is online here, including their innovative online PhD in Palliative Care: https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/health-and-medicine/research/ioelc/

References

1. Wiese CH. Editorial. Palliative Medicine 2018;32(9):1441-42. doi: 10.1177/0269216318795345

2. Gott M, Robinson J, Moeke-Maxwell T, et al. ‘It was peaceful, it was beautiful’: A qualitative study of family understandings of good end-of-life care in hospital for people dying in advanced age. Palliative Medicine 2019;33(7):793-801. doi: 10.1177/0269216319843026