Payment by Results, the mechanism that determines hospital Trust income, is an important and enduring feature of health policy in England. But its critics claim it's a misnomer: that it rewards hospitals according to the number of patients that they treat, rather than the results or outcomes they deliver. Policy-makers have attempted to address this challenge by adjusting payments to take account of some aspects of service quality, but these adjustments are modest and marginal.

In recent years the policy has been renamed as the National Tariff, but the question remains: why isn't hospital income tied more closely to patient outcomes? There's no shortage of support for the idea, from domains as diverse as politics, academia, and patient groups. The fact is that outcomes-based contracts are very difficult to design and implement. So much so that the rhetoric has only rarely turned into reality.

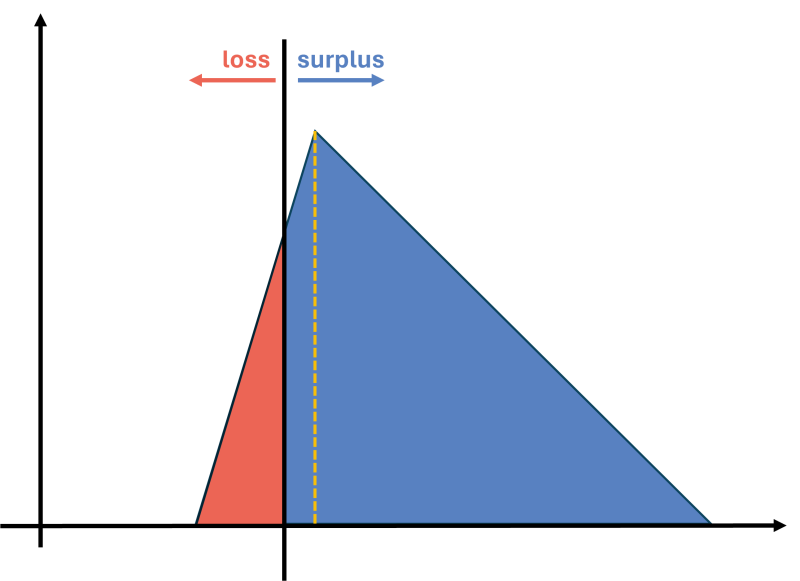

But there's good news. Analysts and researchers have been steadily chipping away at the technical barriers to implementation. Outcome measurement, the raw material of outcomes-based contracts, has matured through the roll-out of national clinical audits and the PROMs programme. Casemix-adjustment methods are increasingly used to ensure that Trusts are compared fairly and incentives to cherry pick 'easy' patients are moderated. And more recently, academics from the University of York have shown how to calibrate the incentives in outcomes-based contracts. This is the last significant piece of the technical jigsaw, and a robust, real-world implementation of an outcomes-based contract now seems feasible.

As doubts about feasibility recede, another, more fundamental question takes centre stage. Should we pay providers based on outcomes? This is not a technical question, but a question of principles, priorities, and fit with the policy and fiscal context. Two challenges dominate health policy today:

-

How to enable healthcare services to cooperate and integrate to improve service quality and patient experience

-

How to increase service capacity, efficiency and equity as the population and the health system recover from the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Outcomes-based contracts could certainly feature in the mix of policy responses to these challenges, freeing up services to innovate, and ensuring that providers maintain focus on outcomes rather than on throughput. But developing and implementing outcomes-based contracts will require considerable effort from NHS England, providers and commissioners, and there are many other issues competing for these agencies’ attention.

If we set aside the option of a wholesale adoption of outcomes-based contracts, which would be premature and unhelpfully disruptive at this point in time, then there are perhaps two rational stances that policy-makers could adopt. The first would be to explicitly postpone decisions on the development of outcome-based contracts for say, three years, until the context is more settled. This would quell the call for outcomes-based contracts, and give providers and commissioners some certainty, but without ruling out the possibility in the future. The second would be to trial an outcomes-based contract for a selected service, evaluating it fully and robustly to inform future decisions about wider roll-out.

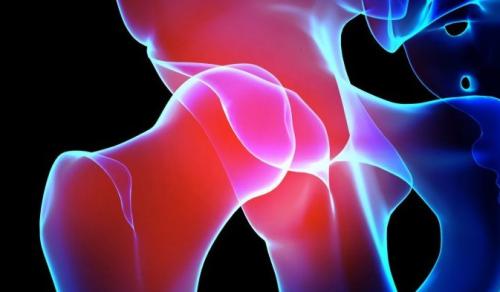

Elective knee-replacement surgery is a prime candidate for trialling outcomes-based contracting. In this paper, we show how an outcomes-based contract for this service might be designed.

Watch the recording from our Insights session below:

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.