Medical history is full of bizarre and gruesome procedures. People have received milk transfusions (milk being the perfect substitute for blood); skulls have been drilled (to relieve pressure and cure headaches); and toddlers have had their teeth cut (to prevent infant death, which often came at the same time as teeth). The list is as long as it is horrifying.

But we know better now. We know that whenever someone claims to have a treatment, it should be tested empirically. Using evidence to sort the bogus from the effective is now the norm in medical science. Evidence-based medicine has its problems, but few of us would want to live without it – and many of us have our lives because of it.

We have advanced. Just not as far as we might like to think. And when it comes to the way services are organised and provided, rather than new drugs or treatments, far too much practice side-steps the use of evidence.

The use of risk stratification tools in primary care illustrates this. And an excellent paper by (the wonderful) Jess Morley and colleagues provides a very important contribution. Their paper - ‘Promising algorithms to perilous applications’ – uses a systematic review to look at the actual effects of the use of risk stratification tools in the real world.

There are many kinds of ‘risk stratification’. This paper does not look at all of them; it focuses solely on risk stratification as it is commonly used in primary care. The basic theory here is ‘employ an algorithm to find high risk patients, then deliver a preventative intervention, and therefore avoid a poor outcome (typically expressed as unplanned care)’.

This is where much policy interest, and encouragement, concentrated. Was it warranted?

Here are the headlines:

- The paper found no change - or even the opposite of what was intended: "Our findings suggest an absence of clinical impact, and indeed a signal of harm in a third of cases".

- They conclude that: "There is an urgent need to independently appraise the safety, efficacy and cost-effectiveness of risk prediction systems that are already widely deployed within primary care."

- Recommendations centre largely upon applying the disciplines of evidence-based medicine: suggesting that regulator clarify their treatment of algorithms.

When it came to risk stratification, the Strategy Unit’s eyebrow has always been raised. Partly because we saw some poor commercial incentives in play; partly because the claims for its benefits seemed implausible on the face of it; and partly because we couldn’t see enough commitment to testing claims using evidence.

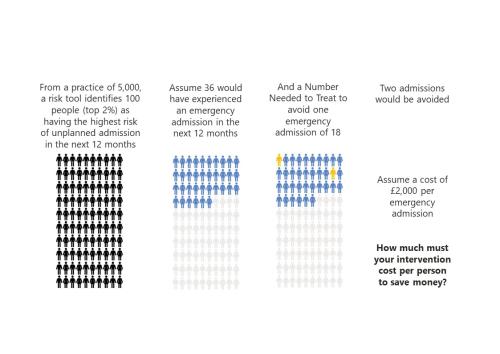

Our take – recently published and summarised here – was that there was a fairly simple way to assess risk stratification before trying it in practice. We used design stage evaluation to lay out what would have to be true for risk stratification to be cost-effective. There was nothing complicated in what we did, and most competent local NHS analysts could have done it if asked.

We concluded that risk stratification tools might very well find ‘the right’ people, but would struggle to prevent poor outcomes once they had. Fairly simple maths suggested that to prevent an emergency admission any ‘intervention’ would need to be incredibly effective. Much more effective than is typical.

We couldn’t see how risk stratification’s claims stacked up in theory, let alone how they might work in practice. The findings of this paper contain an even more bitter pill: risk stratification might be causing harm.

In a sane world, this finding would change practice. Some sort of moratorium on this use of risk stratification might be expected, while Jess Morley and colleagues would be celebrated for showing a way of saving money and preventing harm.

Will sanity prevail?

In some ways, it looks like an uphill struggle. Initial enthusiasm outpaced evidence and risk stratification is well embedded in primary care practice. This would take a lot to unravel. And reading academic papers is a niche sport (hence our attempt to boost this one), so this crucial evidence will struggle to reach the minds that need changing.

And yet…

The way out is known. We know how to use analysis to improve health and reduce harm. We know how to use evaluation to see whether well-intentioned theories fulfil their promise in the real world. The Goldacre Review (also co-authored by Morley!) shows how the NHS could make progress on this. And the Institute for Government also recently concluded that better use of analysis is a route to increasing NHS productivity.

The political cycle is also at a favourable stage. The new government has declared the NHS ‘broken’. The coming months will provide opportunities for noting and jettisoning past failures with far greater ease than was the case before the election.

So there are reasons to be cheerful, but there is no place for complacency. Reading about historical medical treatments is a grim pleasure. It is also instructive. It took a long time, some hard-fought battles, and the creation of specific new institutions and practices, for the norms of evidence-based medicine to become established. The case of risk stratification shows how risky abandoning these norms can be.